At London’s Great Exhibition in 1851, English manufacturer Minton & Co. introduced a new type of earthenware that skyrocketed to commercial success in Britain and the United States. Majolica pottery—exuberant objects glazed with lead ranging from the practical to the purely ornamental—took cues from Italian maiolica glossed with tin as well as the highly decorative work of French potter and scientist Bernard Palissy.

“From its beginnings, Minton majolica was seen as a British triumph of art applied to industry,” explains Dr. Susan Weber, founder and director of the Bard Graduate Center and curator of Majolica Mania: Transatlantic Pottery in England and the United States, 1850–1915, which is now on view through January. (In 1851, Minton won the Council Medal for the technical virtuosity of its new ceramic.) What’s more, Weber says, these new ceramics were accessible to large swaths of the public: “Bold, experimental, eccentric, and gloriously colorful, the ware appealed to a cross-section of classes and budgets, and by the end of the 19th century, could be found in all types of homes—from those of the royal family to the rapidly growing middle class.”

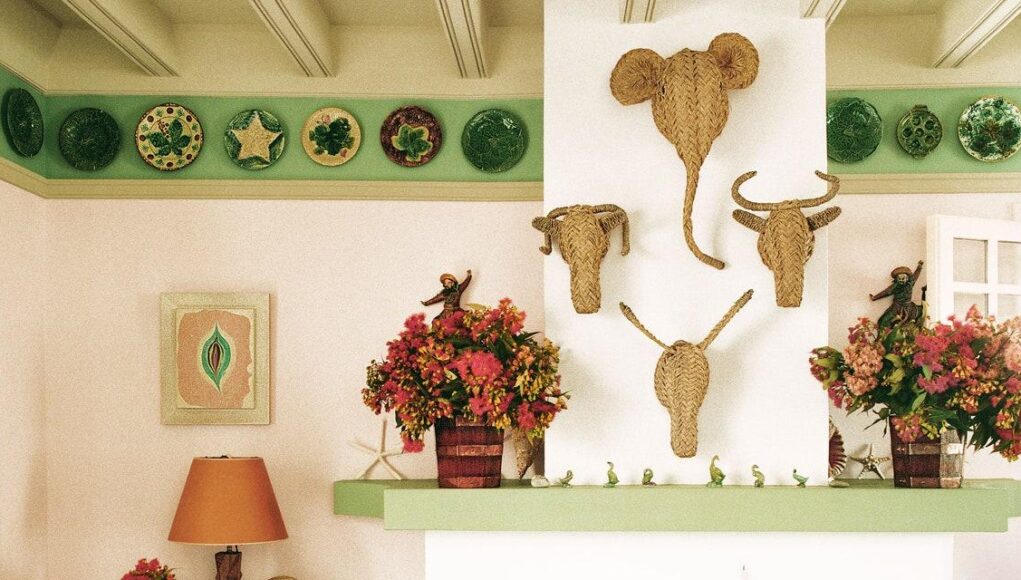

In her Locust Valley, New York, home, Asia Baker Stokes hung a majolica mash-up over a mirror.

During the second half of 19th century, Britain and the U.S. churned out huge quantities of the stuff. The Center shows off this expansive range, from fanciful ceramics for the everyday (think sunflower-emblazoned teapots and a matchbox shaped like a fly) to real showstoppers. One is a Minton jardiniere made for the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1855: “It’s about seven feet tall and decorated with a fantastical mash-up of Renaissance revival forms and painted grotesque ornament,” says research curator Laura Microulis. “And this is the first time it’s being shown in the U.S.”

In 1883, as Weber reveals, its popularity was so vast that historian Llewellynn Jewitt recorded a manufacturer producing 26,000 teapots per week. And in 1895, the British trade journal Pottery Gazette reported on another firm that was putting out two flower pots every minute. Of course, decorative trends come and go: By the mid 20th century the brightly hued ceramics were considered garish, or maybe just a bit too kitsch. But now, as we watch the pendulum swing toward more eccentric, Victorian tastes, or simply more decorative fashions, majolica is back—in museums as well as in some of our very favorite houses.

Majolica vessels by George Jones, who once worked for Minton, in the colorful Sète, France, kitchen of artists Jean-Michel Othoniel and Johan Creten.